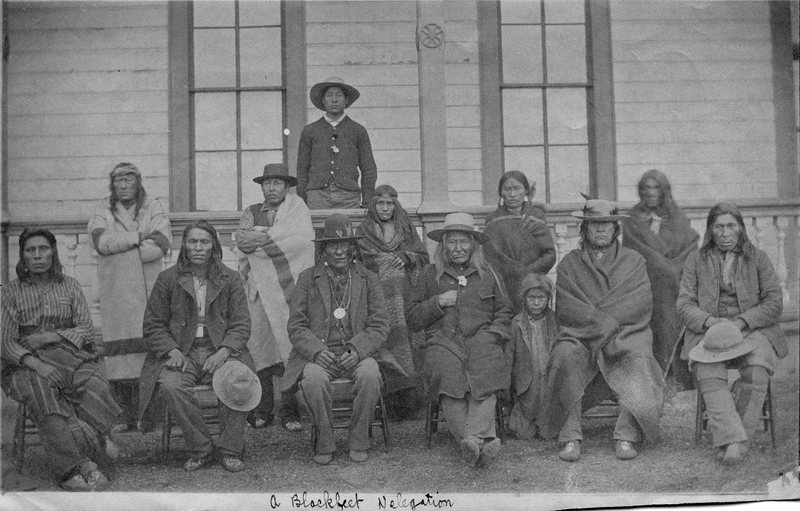

Prando on Blackfeet Reservation

Prando and the Blackfeet:

There are two letters that Father Paul Prando wrote to Father J. Cataldo that details his initial time and efforts amongst the Blackfeet Indians. Through these writings, several observations can be made as to the interactions, general relationship, and desires amongst both parties.

Prando arrives on the Blackfeet reservation in 1881, intent on pursuing the salvation of the “poor savages” through Christianity. It is perhaps important, however, to note the general atmosphere of events that led to Prando finally ending up on the reservation to pursue the conversion of the Blackfeet. Drawing from Larry with his book, we can construct a general concept of how and why the Native American peoples are seeking Christianity at all.

In the years leading up to Prando’s arrival on the reservation, Native Americans are experiencing a decimation of their people, way of life, and culture. Larry makes it quite clear that Native Americans pursue religion with a zeal, making it an integral part of their life that cannot be separated from basic activities necessary for survival. As Europeans arrived, they brought with them diseases that wreaked havoc on the Native American communities nationwide. As more and more people died, Native peoples felt a weakening of their spiritual power. They observed that Europeans seemed to not be suffering the same afflictions and attributed it to a greater spiritual power of the whites. In an effort to make this greater power their own, Native peoples began to pursue Christianity, requesting visits from the “Black Robes” in order to learn. Once Native peoples were forced onto reservations, their ability to connect with their original culture and religion was severely hampered; no longer could they worship the various spirits on their rounds through the Plateau. In Prando’s writings, a summary of a speech by White Calf, the head chief of Blackfeet, is recorded.

“Down to the present time, said [White Calf], the Blackfeet had led a wandering life, without any fixed habitation, but now they are placed upon a Reserve, surrounded by soldiers, hemmed like the waters of a stream which it is feared will overflow; abandoned and left to themselves in this contracted territory, from which they could not stir.”

Presuming an accurate summary of White Calf’s words, it is clear that the Native peoples felt trapped on the reservation. The sense of abandonment could be from several sources: a weakening of spiritual power, a neglect by the new government, or a lack of engagement from the Black Robes. Regardless the source of the abandonment, this situation made the Blackfeet ripe for conquest by the Jesuit Black Robes.

Prando’s View

It can be seen from Prando’s writings that he was quite eager to help save the “poor savages,” as he often called them. He remarks that “the time, so long expected, for the conversion of the Blackfeet, seems at length to be close at hand, and it appears that God is willing to pour down the streams of his mercy and grace upon the hearts of these savages.” In Prando’s mind, he is doing the Native peoples a great favor by working among them and spreading ways of Christianity. He also clearly looks down upon the Native peoples, seeing them as backwards folk who are eager to learn, but so clearly in need of proper instruction.

One of the things that Prando clearly considers is how to most effectively convert the Native peoples. At one point, he remarks that the “Indians need to see something durable attempted, lest they lose all interest and become disgusted.” He further goes on to say:

“The Blackfeet are sunk in want and misery, and, in my opinion, they will have trouble in getting through this winter without dying of hunger. Furthermore, I am persuaded, that the mission among them will not succeed, if we confine ourself solely to spiritual ministrations. These poor people need beyond all to be trained and encouraged to agricultural labors: they themselves now admit the necessity of this, and are anxious to receive instruction. If this method has been pursued in several other missions, and with good results, why not employ it here also, and expect from it a similar success?”

It is obvious that Prando recognizes the dire situation the Blackfeet find themselves in and that he is seeking to use it to his advantage in order to convert them to Christianity. What he perhaps fails to recognize is that it is due to being forced onto a reservation that has placed the Blackfeet in this situation. They must learn the ways of the white man, which is to say, agriculture, or perish. Prando is missing the concept that for the Blackfeet, agriculture is a form of spirituality, though he has clearly observed the link between successful conversion of other tribes and the institution of agriculture.

The view of the Blackfeet

As has been previously noted, the Blackfeet find themselves in a compromising situation. They are dying as a people, due to both disease previously and now due to an inability to pursue the way of life they were accustomed to. There is no knowledge of agriculture, but they now must learn it, lest they die of hunger. There are some interesting views into the part of the culture that is still trying to survive, despite overwhelming odds.

When it comes to Christianity, the Blackfeet are interested in learning, certainly, but perhaps not as wholly committed as Prando seems to think. Of the remarks made by White Calf, Prando has recorded: “You [Prando] will instruct us, and when you have told us anything new, we shall examine it, and if we find that it is good, we will say so” (pg. 36). This commentary implies that the Blackfeet definitely want to try to learn the power of the Black Robes, but not necessarily to convert completely. The Blackfeet will take what works for them and use it as they see fit, and discard what does not. Instead of a complete conversion to Christianity, the Blackfeet seem to be looking more for a merger of their culture and that of the whites, in order to survive and adapt to changing times.

In his second letter, Prando was kind enough to record a few instances of him viewing religious ceremonies performed by the Blackfeet. One of them involves the death of a child and traditional practices of mourning. Judging by the remarks Prando made, it seemed that it was a traditional affair for the survivors to “tear their flesh as a sign of mourning,” (pg. 39). He makes note of slashed cheeks, removed fingers, and commentary of a propensity to mangle limbs. There was also remarks about a possibility of sacrificing two horses as part of the mourning, but another person dissuaded the father from making such a sacrifice (pg 39). The mourning period went on for an entire eight days until Prando arrived, after which he said the prayers for a baptized child. The child was buried with all her belongings, including dishes she had used (pg 39).

Prando also records a small amount about a principle festival, known as the “Medicine Tent,” (pg 39). “The ceremonies and amusements last for several weeks. I [Prando] had only lately come among them, and there had not yet been time enough to instruct them sufficiently; and as besides, they thought that they were rendering solemn honor to the Great Spirit, prudence counseled me not to oppose their action.” (pg 39).

All in all, it is quite apparent that the Blackfeet peoples were still practicing and interested in utilizing their culture, alongside the inclusion of Christianity. They were in a position of needing the help of the Black Robes as they found their own spiritual power waning in the face of Manifest Destiny, but the writings reflect more of a cherry-picking of information and practices as was suitable to the Blackfeet way of life. The Blackfeet were interested in Christianity as a way of survival, but not as a replacement of their own culture.

Source: Peter Paul Prando, "Indian Missions – Rocky Mountain," The Woodstock Letters, Vol. 34, 1883.